Burden of Proof

For Burden of Proof: New work by Lauren Edwards & Kera MacKenzie at ACRE Projects

Curated by Kate Bowen, 2013

In a court of law, opposing parties each carry a burden of proof and must argue their case using, among other things, evidence that can sway jury members to one conclusion or another. Material evidence often plays a critical role in constructing a jury’s sense of the truth and ultimately convicting the accused. Both of the artists included in the exhibition Burden of Proof question the correlation between the reality of an event and the artifacts that are used to reconstruct details about what transpired after the fact.

Lauren Edwards repeatedly re-photographs appropriated images of the desolate and inhuman landscapes presented in the some of the earliest photographs of the Arctic. Originally intended as empirical evidence, these images mark the significance of the sites they depict and, in Edwards hands, simultaneously consider the extent to which photography can accurately describe place, while also highlighting the distance between image and reality. With each representation Edwards’s process shifts the photographic records one step further from the site that was originally documented, thereby emphasizing the nature of evidence, which is always fragmentary and subject to manipulation and misinterpretation. Edwards further interrogates photography’s veracity by manipulating the resulting images as sculptural objects, obscuring or altering the viewer’s point of view. These framing devices draw attention to the limited connection photographs provide to the authentic conditions of the original places they depict. Together, her works assert the image as a site unto itself, one that is necessarily tethered to the moment of viewing.

Kera MacKenzie creates projects that begin with her own first-hand observation of the occurrence of something unexplained. She then reconstructs the experience with imagined evidence as a means to consider various explanations of the mystery of existence. A magnifying glass, which is typically used as a tool to view the minute, becomes an agent of intrigue in her investigation. Requiring only the correct application of light to be activated as a lens, the object as a camera obscura offers an inverted projection of the space around it, which shows the minute as a world unto itself. MacKenzie offers further evidence of worlds unseen in the form of postcards, of her own creation, reminiscent of souvenir cards typically sent from another place and time. The postcards feature images taken from her investigation into the origins of a seed, which mysteriously fell from the ceiling of her studio. Compelled by her curiosity, she searches for answers in places as seemingly disparate as the inside of a market research observation room and the strange man made landscapes of Lake Mead. MacKenzie’s cards are used as proof of her journey to places that are as imaginary and manufactured as the experiences they provide evidence of. Here again, proof becomes a means rather than an end as MacKenzie traces truth through fiction, finding contradicting answers that come to her in the form of new questions.

Exhibition Documentation

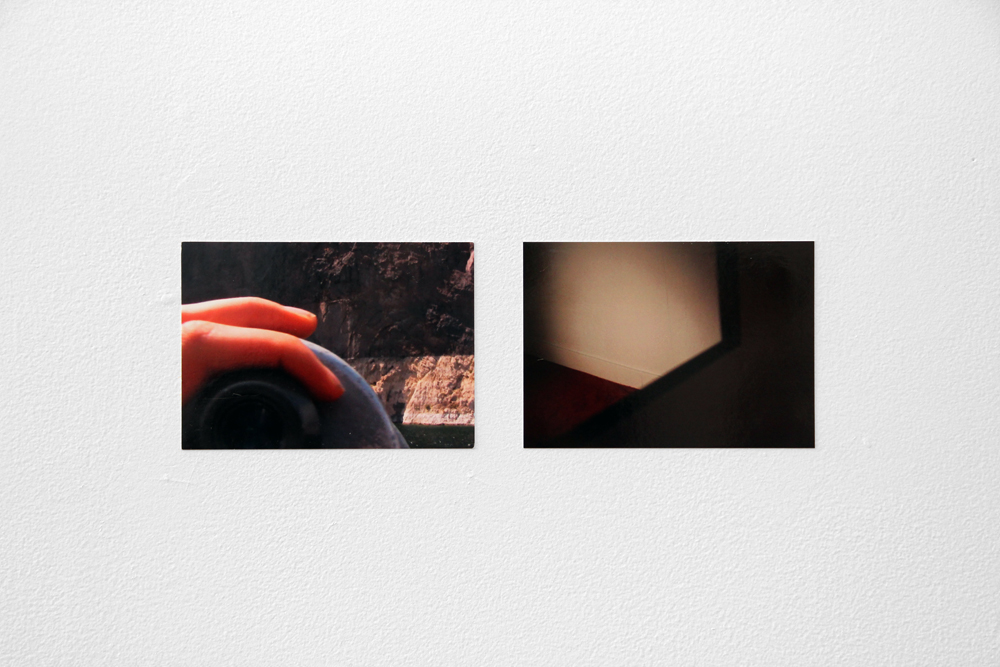

Two postcards

Two postcards on left wall, kinetic sculpture in foreground

Photograph on right by Lauren Edwards

Kinetic sculpture: repelling magnets, gum, nail polish, pedestal

Eight postcards on left

Photograph on right by Lauren Edwards

Eight postcards

Two postcards

Two postcards

Four postcards

Postcard image

One postcard

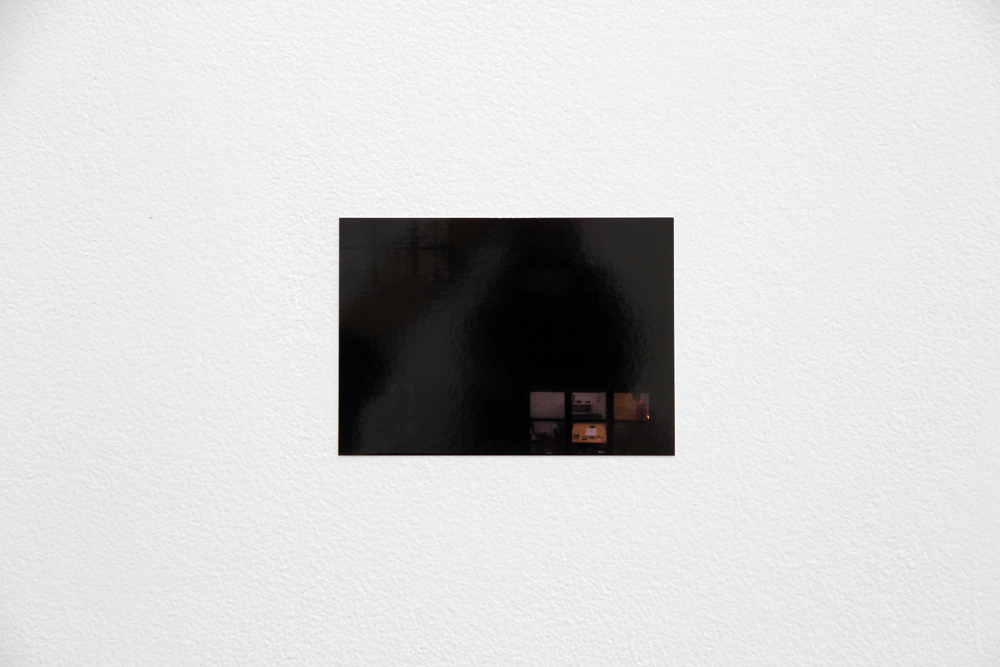

Lens, photograph, pedestal, projected image of gallery opening

Lens, photograph, pedestal, projected image of gallery opening

Press

"Interspersed with Edwards’s ghostly Antarctic vistas, MacKenzie’s photographs and sculptural pieces hinted at impossible narratives, alien worlds, and unseen moving pictures. Abductive Object V, which caught my attention first, shows a hovering, rotating, metallic thing partially inspired by a metal cone in Jorge Luis Borges’s short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius. As Mackenzie explained, “I’ve been grappling with the idea of what it would be to bring back evidence from an imaginary landscape.” The object certainly earns its Tlönic adjectives.

For Distant Viewing, also by MacKenzie, is a mirrored lens mounted on a photograph and pedestal on the far inside wall. "For Distant Viewing is a sculpture but it also feels like a video and a performance to me,” said MacKenzie. “The viewer is asked to lend their figure to the sculpture and in exchange gets to see themselves and the gallery space in an unexpected way."

As I looked into the lens, I could see the inverted image of everything behind me. Behind the upside-down artists and my upside-down companions, I observed a long stretch of 17th Street through the pair of plate glass windows–perhaps an acre, maybe more.

If you lived in the world that corresponds to that image, you’d quickly learn which phenomena are worth perceiving. Observe the stringent parking laws, the relationships between neighbors, the gradual process of gentrification, and the approximate walking distance to the nearest Pink Line stop (about three blocks, not including detours to nearby murals and Mexican restaurants). But inside ACRE Projects, that same red brick sub-block could be inverted, miniaturized, and then examined as an art object. It’s hard to see the reality of city life in an object, even in an object (a lens, an art gallery) that functions as a protean representer of other objects. Maybe that’s a sign that Edwards and MacKenzie have succeeded in complicating the truth of representation.

Wherever you’re standing, look to your left–there may be a thousand acres behind that door." — Nathan Worcester, An ACRE of Glass, The Chicago Weekly

Paul Germanos, Chicago Art in Pictures: March-April 2013, Bad At Sports, April 15

Photos from opening here.

Sketch Documentation

Kinetic sculpture: repelling magnets, gum, sequined fabric

For MDW Fair. Photo: Michael Workman